In recent months, we have become all too familiar with the collateral damage that war inflicts on innocent civilians. The global Red Cross and the Red Crescent movement have been providing critical relief to displaced families in Ukraine and refugees in neighboring countries such as Poland.

The deprivations caused by war have always been severe, including in our own country when the Civil War was winding down in 1865 and citizens in Southern cities such as Richmond, Virginia, were homeless and starving. In those days, there was not yet a Red Cross, but an earlier organization known as the Christian Commission performed many of the life-saving duties that the Red Cross would later assume.

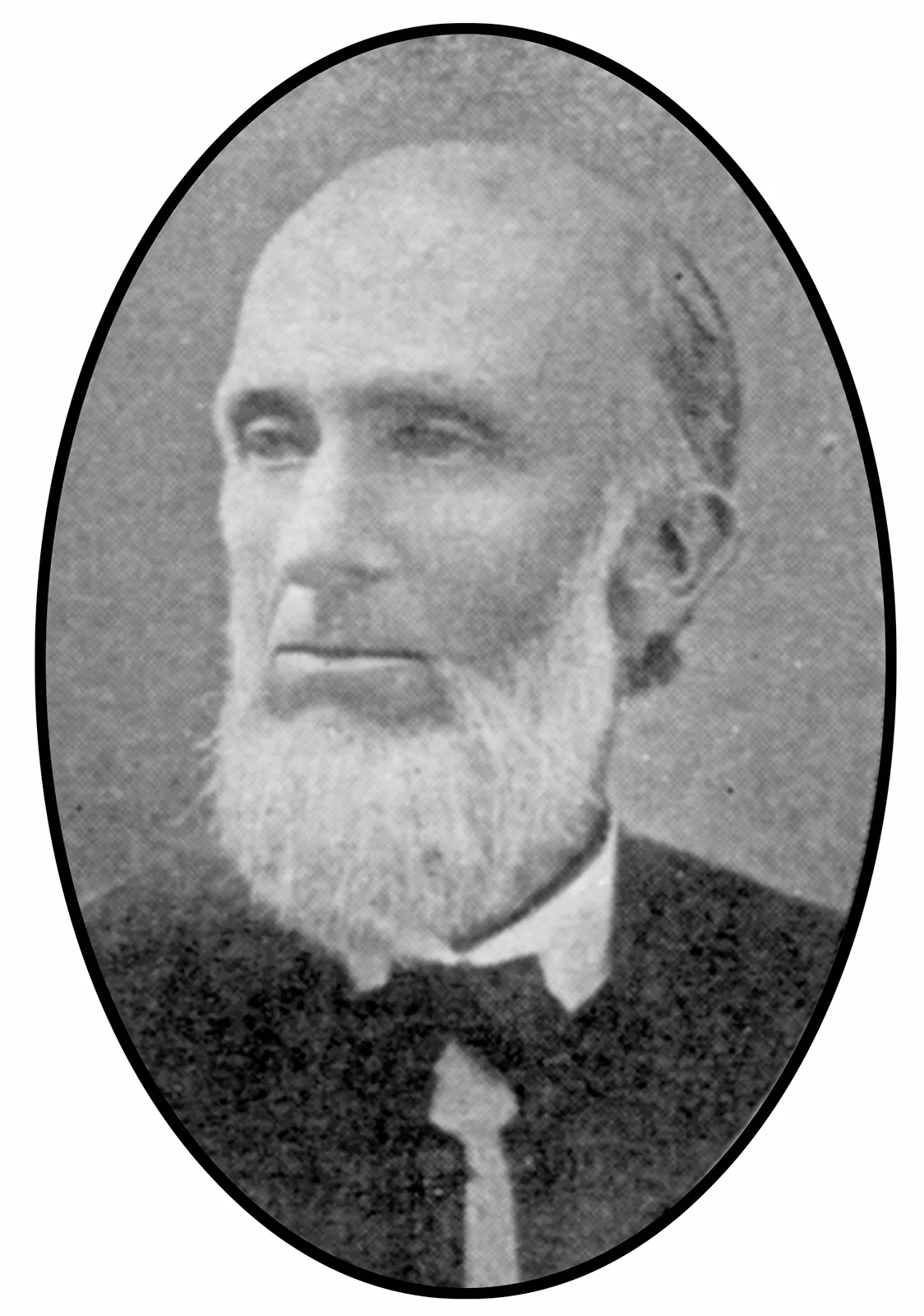

In February 1865, a Monmouth minister answered the call, volunteering as a field delegate for the Christian Commission. The Rev. Robert Clayton Matthews, pastor of the First Presbyterian Church, traveled by train to the East Coast and entered upon his work with the Army of the James, dug in the trenches surrounding Richmond. But scarcely had he begun work when a telegram advised him that his 6-month-old son, Robbie, was deathly ill, so he boarded a train back to Monmouth, where he remained until his child’s death on March 2.

Immediately returning to Virginia, Matthews resumed his duties, distributing stores to hospitals, circulating literature to soldiers, writing letters for the sick and wounded, providing news from families back home, and preaching. As the Army of the James advanced on Richmond, he would soon find himself in the middle of a massive effort to provide relief to the local citizens.

Entries to his diary, which was retained Matthews’ descendants years after his death, paint a picture of the work Matthews performed in the spring of 1865:

March 30, 1865 — Skeined 350 skeins of thread. Last night tremendous cannonade off to the left, flashes and shells visible — a heavy and almost continuous road — no word certainly from the fight yet. Peach blossoms and strawberry blossoms out in full today. Attended meeting in the 115th. A good company out and an impressive service.

March 31 — Gave to Brother Baston 9 copy books, 8 spellers, 3 cans of milk — to Chaplain Higginson 70 envelopes — to brother Moore ½ dozen pen holders — Skeined 250 skeins of thread.

April 2 — Heavy fighting over on the Bermuda Hundred’s front, ominous of great success of our troops. Preached in the chapel tent of the 115th U.S.C. to a full house — good attention.

April 3 — Awakened by the cannonade and a tremendous explosion. Early in the day our cavalry scouts dashed through our lines and discovered that the rebels had evacuated. Our troops soon had possession and pushed on in pursuit and took Richmond. I went over to the Rebel works and went through them with the troops — tremendous cannonade towards Richmond. Our troops were treated cordially by the citizens of Richmond. Can not tell where the Rebels have gone. Richmond, or a part of it, is burning now. In the evening Mr. Williams came an scolded at a great rate about us Delegates going to Richmond.

April 4 — After breakfast and prayers, commenced packing — went to Richmond. I rode five miles. Let a woman and boy take my place the balance of the way. It is eight miles.

April 7 — Assigning Delegates to Hospitals. A crowd of hungry applicants rushed in upon us, pleading piteously for something to eat. Over 1,900 persons supplied with food for one day. Such a scene I have never witnessed. In the evening the more respectable ladies, who were ashamed to come in the day time, came to ask for food. Took a telegram for Mr. Stuart to the office calling for $10,000 worth of flour.

The diary entries themselves do not convey the importance of the work that Matthews performed. A story in the Richmond Whig of April 19 adds more weight to his accomplishments:

“The gentlemen who are associated in the United States Christian Commission on Monday issued to the needy of Richmond to meet their actual necessities ten thousand seven hundred and twenty-one rations of flour, beans, etc. Much credit is due to the laborious industry of Dr. R. C. Matthews and other gentlemen prominent in the enterprise.”

Matthews was born in Shepherdsville, Virginia, in 1822. His father was a professor at the New Albany, Indiana, Presbyterian seminary, which would later move to Chicago and became the McCormick Theological Seminary.

The younger Matthews graduated with honors from Hanover College in Virginia, studied law, then moved to Fairfield, Iowa, where he practiced law for a time. He then moved to Mississippi, where he was engaged in teaching for a few years. In 1846, he married Louisa Martin in Indiana, and the couple returned to the South, where Louisa died in 1849. During this time, Matthews had converted to Christianity, and after the death of his wife he entered the New Albany seminary, where his father taught. After being ordained in 1850, he was invited by the Presbyterians of Monmouth to become their pastor.

Matthews preached his first Monmouth sermon in December 1851 in the courthouse, as the Presbyterian church on South Main was not yet completed. He would serve as the church’s pastor for 30 years, heading up a building committee that would construct a massive gothic brick church at the corner of South 2nd Street and East 1st Avenue.

In 1852, Matthews married Isabella M. Ickes of Bloomfield, Pennsylvania, the sister of Susan Harding, who was the wife of Monmouth capitalist and future Civil War general and congressman, Abner Clark Harding. The couple would name one of their daughters Susan Harding Matthews and one of their sons Abner Clark Harding Matthews.

In 1857, Matthews became a charter trustee of the new Monmouth College, serving as an influential member of its governing board until his 1870. He was so respected that when an out-of-town church offered him a job, fellow college trustee Ivory Quinby declared “that sooner than Dr. Matthews should leave the town, he would personally pay his salary for the sake of seeing him walk the streets; that his daily life in Monmouth had done more to elevate the youth and advance morality than all the other preachers of the place combined.”

One Sunday in 1881, as work on the new Presbyterian Church neared completion, Matthews preached two sermons. Speaking about the upcoming removal of the congregation to a new sanctuary, he said, “the old church and its old pastor will pass away together.” His words would prove prescient.

The following Tuesday, after inspecting the new building, Matthews was out in his yard with his son shooting arrows at a target, when he was struck with a fatal heart attack. When his death was announced, the Monmouth College bell and the bell of his church each tolled 59 times, marking the number of years of his life. Six respected pastors collaborated in his eulogy, prior to his interment in Monmouth Cemetery.

Matthews had two children by his first wife and seven by his second wife. The children from his earlier marriage both had interesting careers: Bessie was a Presbyterian missionary, spending 10 years in Sitka, Alaska. John W., a Civil War veteran, was twice elected Warren County state’s attorney. Tragically, he disappeared in Chicago in November 1896, and his body was never found.

by Jeff Rankin

Editor and historian for Monmouth College. Avid researcher of western Illinois history for 40 years. FB and Twitter. jrankin@monmouthcollege.edu